The Disposable Software Paradox

The cost of building software is trending to zero. But in a sea of infinite tools, the hardest part is deciding what to choose.

We are living through a tectonic shift.

The cost of building software is plummeting. With agents becoming increasingly capable, we are entering an era where almost anything can be built, by anyone, almost instantly.

But as I’ve been experimenting with this new reality - generating apps, testing workflows, and seeing others do the same - a strange paradox has emerged.

If software is disposable, how do we decide what’s worth keeping?

The Vibe Coding Trap

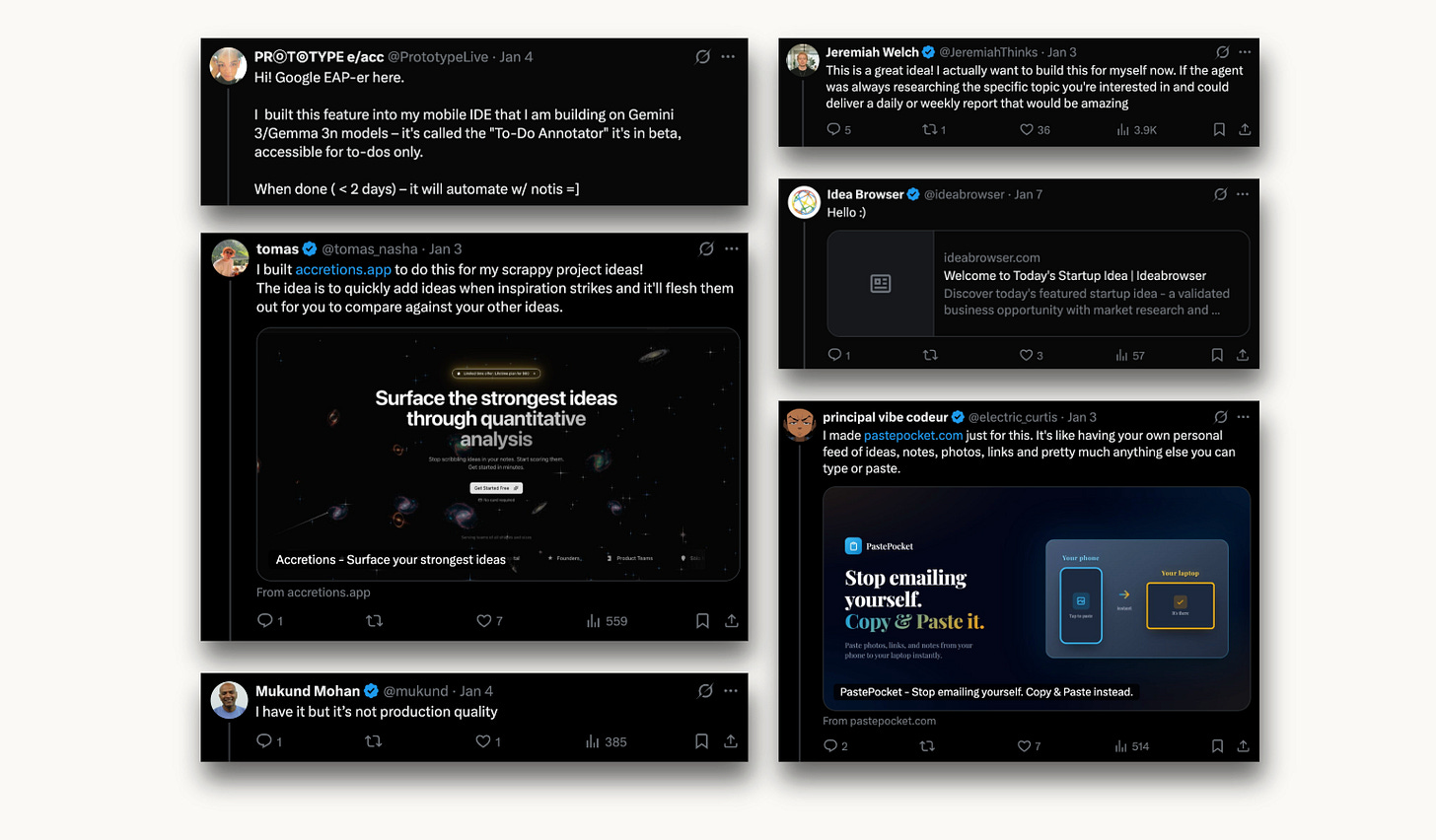

I tweeted the other day about having too many ideas and not enough time. The response was overwhelming. People flooded the replies with their own workflows, tools, and even apps they had built specifically to solve my problem.

It was incredibly cool to see that level of creativity. But as I looked at all these new tools, I realized something: I don’t have time to try them all.

And more importantly, I don’t know if I should.

When the cost of production goes to zero, the volume of noise goes to infinity. We are about to be drowning in “vibe coded” apps—software built in an afternoon to solve a niche problem. But just because an app solves a problem today doesn’t mean it deserves a permanent place in my life.

The Maintenance Question

Software isn’t just code; it’s a commitment.

When I choose a tool for my workflow - whether it’s for note-taking, project management, or even just capturing ideas - I am making an investment. I am investing my time to learn it, my habits to integrate it, and most importantly, my data to fuel it.

In the old world, the high barrier to building software acted as a filter. If a company had built a robust product, it signaled a level of seriousness. It signaled that they were invested in maintaining it for the long haul.

In the new world, where a solo founder (or just a curious person with an afternoon free) can spin up a fully functional app, that signal is gone.

I found myself hesitating to try a new idea-capture app recently. Why? Because I don’t know where my data is going to live. I don’t know if the developer will get bored next month and shut down the server. I don’t know if this is a business or a weekend experiment.

The “bus factor” used to refer to a key engineer getting hit by a bus. Now, the bus factor is simply the developer losing interest.

The Search for Durability Signals

This is why I’ve found myself becoming more picky about the tools I adopt that require a more serious investment of my time.

It’s not just about features anymore. I am constantly scanning for signals that the tool - and the team behind it - will exist in a year.

I look for social proof: Are other people I respect betting their workflows on this? That community momentum is often the best insurance policy against a product dying.

I look for backing: Is there a notable investor or a company with a track record behind it? It’s not a guarantee, but it’s a signal that they have the runway to keep the lights on.

And I look at the infrastructure: Is this built on a platform that has longevity?

The Forkable Future

This leads to a trend I’m seeing pop up more and more: The return of the fork.

This isn’t a new concept - open source has been around for decades. But AI is making the ability to “own” and modify code accessible to a much wider group of people - at the application and end-user level. We are seeing platforms explicitly lean into this pattern. Opal, for example, is built entirely around this dynamic - allowing users to take an AI mini-app, fork it, and remix it to fit their exact needs.

In a world of disposable apps, this might be the ultimate form of trust. If someone builds a great tool but loses interest, I can just take the app and maintain it myself. In that scenario, longevity is on me.

The upside is total control. I can trust myself not to shut things down. The downside, of course, is that I’m now the maintainer. If the original builder ships a brilliant update, I might miss it unless we figure out better ways to merge upstream changes into personal forks.

We might be heading toward a future of “self-healing” or “self-improving” apps, but until then, we are stuck with a trade-off.

As we flood the market with disposable software, it will be interesting to see if a bifurcation grows:

Ephemeral Utility: Tiny, single-purpose apps that we use once and discard.

Enduring Systems: Platforms that have earned our trust through community, backing, or the ability to be owned and forked.

For the builders out there (myself included), the challenge isn’t just “can you build it?” The answer is now almost always yes. The challenge is, “can you convince me to use it?”

Can you prove that you are serious? Can you prove that my data won’t disappear? Can you prove that this isn’t just another piece of digital litter in a world that is rapidly filling up with it?

The barrier to entry has fallen. But the barrier to trust has never been higher.

🔒 Bonus: The Spark File (Raw Notes)

Welcome to The Spark File, an irregular series where I share my unfiltered thoughts, early observations, and the messy “work in progress” ideas rattling around in my mind. This is the stuff that isn’t fully baked yet, but feels too interesting to keep entirely to myself.

Thanks for being a paid subscriber. As a thank you for supporting my work, I wanted to give you early access to my raw thinking - the unpolished observations and hypotheses that I’m still chewing on…

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the velocity of shipping - specifically, what enables speed and, more importantly, what actually gets built when the barrier to building drops.

Two data points have been bouncing around my head this week.

1. The Recipe for the Claude Cowork Launch

Anthropic launched Claude Cowork this week. The headline is that they built it in about a week and a half, with Claude writing the vast majority of the code.

First of all, that’s just impressive - and on the surface, that might seem like a stretch of a statement - but looking under the hood (and borrowing some insights from Claire and Lenny), there is a specific recipe that can enable this kind of velocity:

The Foundation was baked: As Claire noted, this feels like a UI wrapper on top of what already existed with Claude Code. They weren’t starting from zero; the hard plumbing was done.

The Distribution was solved: They already had the installed app base. They weren’t fighting for deployment or reach on day 1.

The “PRD” was crowd-sourced: Back in October, Lenny published a piece on “50 use cases for non-technical people.” In a world where AI writes the code, that article basically acted as the Product Requirement Document, along with the logs of existing users. They had a blueprint of what people were trying to do in “non-code” ways, and they just productized it.

When you have the plumbing, the distribution, and a clear set of features defined by user behavior, AI lets you compress months of work into days.

2. The “Vibe Code” Experiment

The second data point is personal. Our team at Labs just came back from the holidays with a “light meetings week” - we basically encouraged everyone to just “vibe code,” build stuff, and see what happens. We also shared with eachother what we had built over the break.

I made Mosaix - a Photo Mosaic app (because I, like everyone else, am drowning in family vacation photos and wanted a new way to reimagine those memories). When we did demos, I noticed a pattern. The things people built weren’t calculated market plays. They were deeply personal. They built things they cared about. They built things they wanted to exist, not because they expected the world to use them, but because they found them interesting or fun. And in a lot of cases, so did their friends and family.

The Hypothesis

This leads to my rough theory on “what gets made.”

The barrier to creation is getting incredibly low, but it’s still not nothing. The average person isn’t just going to start shipping software randomly. However, the barrier is now low enough that passion is becoming the primary shipping mechanism.

If you care deeply about a problem - whether it’s visualizing your photo library or automating a specific workflow - you can now build the solution. If you can articulate the problem (like the use cases in Lenny’s article), the AI can handle the execution.

We are moving toward a world where software isn’t just built for “users” - it’s built by people for themselves, fueled purely by personal interest. The velocity comes from the tools, but the direction comes from what we actually give a shit about.